Paradise

Recurring in many cultures, the idea of paradise as a better place set in the past, the future, or perhaps just over the horizon would seem to be hard wired into human psychology. In the case of the Abrahamic religions, paradise is the archetypal setting for the original sin, when the allegorical figures of Adam and Eve transgress God's law and seek knowledge for themselves. Consequently, humanity is evicted from the garden and the unity of nature, humanity, and God is rent asunder. Adam and Eve are sentenced to agricultural labor and their son, Cain murders his shepherd brother and constructs Enoch, the first city.

Anthropologically, paradise is a signifier of the agricultural revolution and its concomitant sense of lost unity with nomadic biorhythms. It is also the poetic and allegorical setting for ongoing questions as to humanity's role in relation to all other forms of life. For example, in variations of Genesis it is possible to conclude that we receive God given dominion over nature, or alternatively, that we are situated in the garden and instructed to "dress and keep it".

Whether the Garden of Eden is a metaphor for the whole world or a discrete place within it has troubled theologians, explorers and mapmakers for centuries. As a myth its center point was simultaneously the well spring of the Tigris, the Euphrates, the Ganges, and the Nile; as a real place it probably grew out of oral history related to the once exceptionally rich biodiversity of the landscape now submerged under the northern reaches of the Persian Gulf. Now, as Judith Schalansky writes "[t]here is no untouched garden of Eden lying at the edges of this never-ending globe. Instead, human beings travelling far and wide have turned into the very monsters they chased off the maps". 1

Utopia

Evicted from the garden, humanity could only turn towards the city. As a continual expression of plans for a better world, the city is the ever-imperfect expression of the utopian impulse. Derived from a combination of eutopos — the place where things are well and outopos — no place, the neologism utopia was coined by Sir Thomas More in 1516. The literary genre which describes a fictional, better world so as to positively inspire change in the extant one, utopia has its roots in Plato's 'Republic', a militant but theoretically perfect society ruled by philosopher-kings.

During the 18th and 19th century, utopian thought sought primarily to harness the power of machines to bring about the good life, but as the industrial revolution wreaked its havoc it was John Stuart Mill who, in 1868, first used the term 'dystopia', utopia's alter ego. Although opposite representations of the future, both utopia and dystopia seek to avoid the same thing — more of the same.

In the latter half of the 20th century a third topos 'ecotopia' emerged in literature. In broad terms, ecotopia is primarily concerned with the spiritual reconciliation and material integration of natural and cultural systems so as to avoid a future that is otherwise cast as an ecological apocalypse. This sensibility manifests itself now in real designs and practical policies to make contemporary cities less wasteful and more sustainable.

Whilst useful as critiques of the status quo, as history attests, when utopias become real they tend inexorably toward fascist states, for it is only through such absolute power that utopia's stringent standards and homogeneous mandate can be maintained.

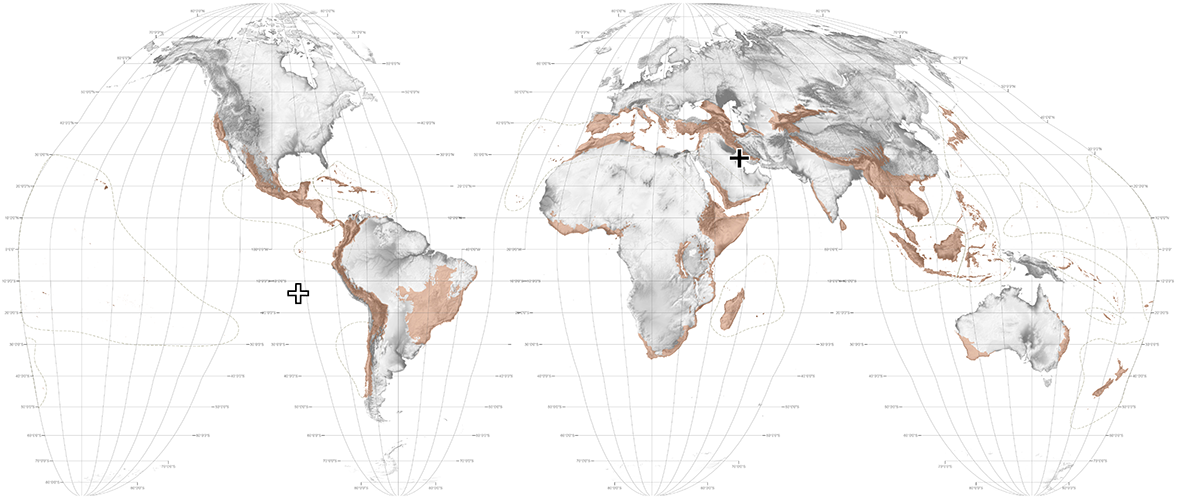

A typical utopian ploy has often been to locate the new improved society on a fictional island. As such, on the attached map we have located utopia somewhere off the coast of Peru, not far from where it is thought that More located his original.

1 Judith Schalansky Atlas of Remote Islands (London, Penguin Books, 2009), 19.

1. Hotspots

Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, "The Biodiversity Hotspots," http://www.cepf.net/resources/hotspots/pages/default.aspx (accessed July 1, 2014). Data made available under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode.